Tolerances that are too tight can easily increase production time, lead to more expensive machining, and worse yields. That's why, from a functional aspect, it's always a good idea to ask yourself if a part really requires the closest tolerances. If the part meets these requirements, we'll be able to manage even the most stringent tolerances. If it doesn't, lowering tolerances where necessary can greatly enhance the part's machinability in terms of both time and cost.

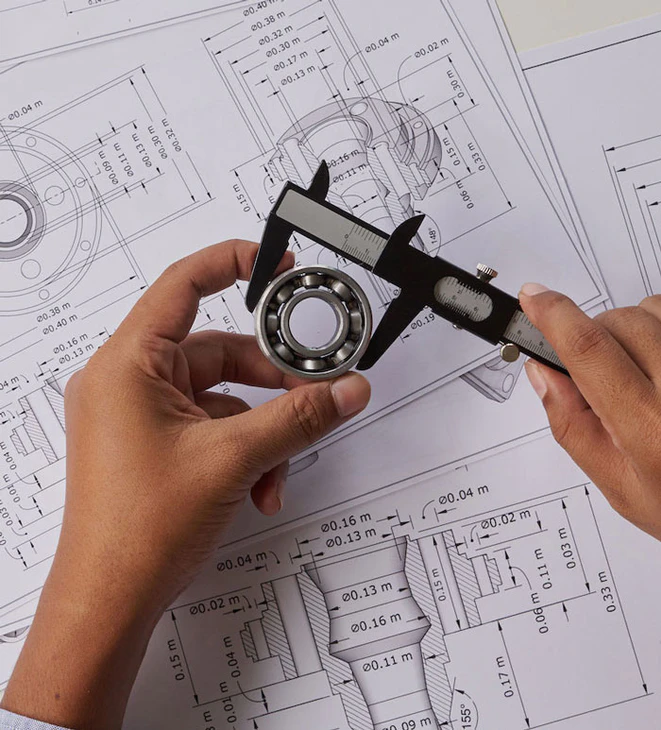

Tolerances refer to the amount of dimensional change that an object can tolerate while still functioning properly.

They can refer to the shape of a portion, such as flat, straight, or circular, as well as its placement, such as symmetry or concentricity. Feature orientation, profile, and runout are examples of other sorts of tolerances.

Overly tight tolerances have two disadvantages: time and money. For example, after a particular dimensional threshold is reached, hole sizes will necessitate the use of unique or specialist tools, which will add to the cost. To meet the tightest hole size standards, the machine shop may have to move from machining to electrical discharge machining (EDM), jig boring, or water jet cutting, which will add time and skilled labour expenses.